Kom women in the Bamenda Grassfields of North West Cameroon launched a three-year period of revolt between 1958 and 1961 known as the Anlu Rebellion, which was provoked by the colonial imposition of vertical contour farming. Through public singing, verbal insults, dancing, demonstrating in public and seizing control of resources, women intensified their anti-colonial protest and troubled political power.[1]

The origins of the women’s rebellion lay in pre-colonial patterns of female organisation and responsibility for public affairs. It centred on the restricted exploitation of resources through the British establishment of the Kom/Wum Forest Reserve in 1951. The resulting enforcement of cross-contour cultivation challenged and restricted the traditional methods favoured by rural women. Also, factors such as the introduction of Christian doctrine and other social changes orchestrated by the Western-educated elite exacerbated social segregation and attacks on tradition and customs, adding more fuel to the fire of the Kom women’s grievances. Recruitment of labour for commercial plantations was also socially destabilizing and gender-insensitive. As a result of all these issues, the Kom women formed themselves into groups to torpedo the efforts of the colonial officials to introduce new farming rules.[2]

The Bamenda Western Grassfields of Cameroon have historically witnessed women’s mobilisation for diverse reasons. In the different fondoms (kingdoms) there were and still are revered, gracious and preeminent women’s societies. These societies often met on Sundays or following the death of a member’s husband, or when an emergency demanded. Their meetings and other avenues facilitated the dissemination of information to women outside the groups and to the wider community.

Other women used their traditional rotating associations to assist one another in the cultivation of crops and to provide diverse forms of material assistance before the introduction of the money economy in the colonial period. To facilitate the resolution of critical issues, women elders of respective ethnic groups also met at the request of a queen mother. Women were generally mobilised from the level of the compound, lineage, quarter and village to carry out certain projects, such as the clearing of footpaths leading to farms, different quarters and neighbouring villages.

The advent of colonisation overtly politicised many of these women’s groups, turning them into associations through which grievances were expressed in various forms against the ruling authorities. This was the case with the anlu (mobilisation) of Kom, which initially was meant to sanction the exiling of people who had become an irritation to the community.[3] An anlu is signalled by a woman doubling up in an awful position and making a shrill sound, which she breaks by beating on her lips with four fingers. Any woman recognising the sound does the same, leaving whatever she is doing and running in the direction of the first sound. Eventually women pour into the compound of the offender singing and dancing, and desecrate it through indiscriminate urination and defecation. If this occurs early in the morning, there is enough excreta and urine to turn the compound and its houses into a public latrine. Also, women exhibit the private parts of their bodies, as the public sight of their vaginas by Kom or Laimbwe man was considered an ill omen .[4] In addition the women not only stripped naked but used their breasts as guns of war.

This use of cultural symbolism was so powerful that even though the British seemed—or perhaps pretended—not to have understood the message, they could not deny its power. Many of the overzealous military men whom they sent to the area to quell the women’s protest could not stand the sight of the women’s nakedness and simply fled for their lives.[5]

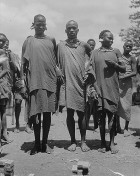

The use of the whistle among Laimbwe women complemented the production of sounds that indicated preparation for war. Women employed these symbolisms, including ululations followed by dancing, which called forth an emotional response from other women, against acts of the administration considered unpardonable. They wore regalia of torn male clothes, shirts, trousers, dry banana leaves and fresh creeping plants, and painted their faces with charcoal and wood ash to send a message of liberation. One of the reasons for such dress was to ward off men from trying to subjugate the women to their whims and caprices during the period of the revolt. Their adoption of male dressing was a particular challenge to masculinity, epitomised by the male-centred colonial dispensation.

In Kom, women also organised mock burials of leaders who supported the implementation of the new farming rules that the women opposed. Mock burial before one dies, a tradition of the western Grassfields region, usually sends shock waves down the spine of the victim and his or her family members and sympathisers. This is how the women effectively shut down markets and defied colonial and traditional authorities for three years.[6]

The nature, level and coordination of the women’s revolt from bottom to top, top to bottom, village to village, one geographical region to another and within the same ethnic group contributed immensely to its success. In many instances, the colonial administration either underestimated or never fully recognised the women’s coordinated activities. Before long, these activities destabilised the colonial administrative machinery, partially disempowering it economically.[7]

The efficiency of the mobilisation of Kom and Laimbwe women was due to several socio-economic and cultural factors. In both territories, especially in Kom, women had started organising protests from the 1940s against the destruction of food crops by the cattle of Fulani herders. These protests increased with time and forced the women to occasionally stage open demonstrations to publicize their plight. Secondly, the women used their existing structures of organisation to their advantage, that is, their village, ethnic and family networks, to create layers of coordination that were strictly respected. The flow of information vertically and horizontally was one of the strongest uniting forces in the women’s movement in these fondoms.

Another critical success factor in the rebellion was the carefully chosen, empowered and coordinated leadership. For every community, there was a recognised local leader who worked closely with her subordinates. This local leader also worked very closely with other selected leaders from the different wards or quarters of the village, and solicited at all times the support of other leaders in neighbouring communities.[8] In the villages and quarters of Kom and Laimbwe, women leaders provided inspiring guidance for all women to emulate. Leadership was also in the form of inter-village meetings. Through these meetings, the different delegations were briefed on new developments and whether or not these developments would have an impact on them.

Thus the three main factors that contributed to the women’s revolt in the western Grassfields of Cameroon were cultural symbols, well-coordinated leadership and the force of the leadership’s character and charisma. Although the women’s revolt eventually gave way, it did not fail to achieve anything. Rather, through their revolt, the Kom women proved that they were more organised than it had been thought and that their leadership was grounded in grassroots’ support and coordination.[9] Subsequent to these activities, women in Cameroon played an active role in the struggle for independence, as well as in the unification of their country.[10]

—

Footnotes:

[1] Tadesse, Z. (2002). In search of gender justice: Lessons from the past in unravelling the “new” in NEPAD. Paper presented at the African Scholars’ Forum Meeting. Nairobi, Kenya.

[2] KamKah, H. (2011). Women’s resistance Cameroon’s Western Grassfields: The power of symbols, organization, and leadership,1957-1961. African Studies Quarterly, 12(3), 67-91.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Dahbany-Miraglia, D. (2003). Feminists born, feminists bred. Women and Language, 26(1).

[5] Shankin, E. (1990). Anlu remembered: The Kom women’s rebellion of 1958–61. Dialectical Anthropology, 15 (2-3), 159-180.

[6] Ibid.

[7] KamKah, H. (2011). Women’s resistance.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Tadesse, Z. (2002). In search of gender justice.